Fast Gated EPR Imaging of the Beating Heart: Spatiotemporally-Resolved 3D Imaging of Free Radical Distribution during the Cardiac Cycle

Zhiyu Chen, Levy A. Reyes, David H. Johnson, Murugesan Velayutham, Changjun Yang, Alexandre Samouilov, and Jay L. Zweier

This is an author's electronic pre-print of the following publication. MRM allows pre-prints to be shared through individual author's websites; for terms, please see this website's license. Please cite the published work as:

Chen Z, Reyes LA, Johnson DH, Velayutham M, Yang C, Samouilov A, Zweier JL. Fast gated EPR imaging of the beating heart: Spatiotemporally resolved 3D imaging of free-radical distribution during the cardiac cycle. Magn Reson Med 2013;69(2):594-601. PMID: 22473660. DOI: 10.1002/mrm.24250.

Address for correspondence: Jay L. Zweier, MD. jay.zweier@osumc.edu

Abstract

In vivo or ex vivo electron paramagnetic resonance imaging (EPRI) is a powerful technique for determining the spatial distribution of free radicals and other paramagnetic species in living organs and tissues. However, applications of EPRI have been limited by long projection acquisition times and the consequent fact that rapid gated EPRI was not possible. Hence in vivo EPRI typically provided only time-averaged information. In order to achieve direct gated EPRI, a fast EPR acquisition scheme was developed to decrease EPR projection acquisition time down to 10 – 20 ms, along with corresponding software and instrumentation to achieve fast gated EPRI of the isolated beating heart in as little as 2 to 3 minutes. Reconstructed images display temporal and spatial variations of the free radical distribution, anatomical structure, and contractile function within the rat heart during the cardiac cycle.

INTRODUCTION

In vivo or ex vivo electron paramagnetic resonance imaging (EPRI) has been established as a powerful technique for determining the spatial distribution of free radicals and other paramagnetic species in living organs and tissues (1-11). Conventional EPRI is based on continuous wave (CW) signal detection. The sample is placed in a resonator which is used to apply fixed-frequency microwave irradiation while the magnetic field is swept past the resonance(s). The EPR spectrum is detected as changes in the reflected signal returning from the resonator as a function of magnetic field, and is recorded as the first derivative of the absorption spectrum. Spatial information is introduced into the spectrum by applying a continuous, one-dimensional magnetic field gradient across the sample, at the same time as the magnetic field sweeps (12-15). Although EPRI has been an established technique, there still are numerous constraints which have limited and/or compromised applications of the EPRI technique. For example, CW-EPRI can only be acquired as projections by definition because it is a form of tomography with up to 3 spatial axes and possibly a spectral-spatial axis. These axes are resolved by magnetic field gradients using tomographic techniques developed by Lauterbur et al.(16) The acquisition time for a single projection is limited by sweeping the magnetic field to acquire different portions of the projection. EPRI generally requires relatively long acquisition times typically of minutes, with projection acquisition times of >2 seconds. Therefore, the problems associated with organ movement, such as the contractile motion of the heart or respiratory motion with breathing, have considerably limited image resolution and made it difficult for EPRI to visualize the critical periodic motions which occur in living systems (3,5-9). Consequently, in vivo EPR spectroscopy and imaging usually provides only time-averaged information. This results in a loss of information regarding the temporal and spatial changes due to cardiac and/or respiratory movements for in vivo animal model studies. These time-dependent spatial movements also result in artifacts and loss of accuracy in acquired images. Hence, to date most EPRI experiments have been restricted to biological systems with limited motion, and information regarding the effects of cyclic variations such as those during the cardiac or respiratory cycles has not been possible to obtain.

Therefore, an important long term goal in EPRI has been to develop instrumentation and approaches to enable rapid gated imaging, which will expand the application domain of EPRI to the study of living systems where temporal and spatial changes are a significant limiting factor. However, this goal has been quite difficult to achieve because of the long projection acquisition time in EPRI. In previous work related to gated EPR spectroscopy acquisition, we reported that rapid scan EPR spectroscopic measurements were possible enabling gated acquisitions over a cardiac cycle (17). Subsequently, Testa et al. (18) developed an apparatus that permits synchronization of the signal acquisition from a moving sample in EPRI experiments. We reported an approach to perform gated EPRI on perfused and paced beating rat hearts with conventional data acquisition (19). Prior work with gated cardiac EPRI (18,19) was an indirect acquisition method because one complete projection cannot be directly acquired from one magnetic field sweep for the reason that the magnetic field sweep time is much longer than a cardiac cycle. Subsequently, one set of complete projection frames corresponding to different time points in a cardiac cycle could not be directly acquired over one cardiac cycle due to the long magnetic field sweep time and projection acquisition time. In prior work, instead a complete projection must be indirectly acquired over multiple cardiac cycles with acquiring only one data point from each cycle. The sweep magnetic field was stepped up cycle after cycle, and only one data point on the projection corresponding to that magnetic field value was acquired in one cardiac cycle for each projection frame. Projection acquisitions could not be conducted during consecutive cardiac cycles, because every other cycle was used for field advance and stability. Hence, half of the cardiac cycles were wasted doubling the total acquisition time required. The typical data acquisition time of this approach was 20–25 seconds per projection, and total acquisition time was 64 minutes (19). In addition, due to the very long acquisition time for acquiring a complete sequence of cardiac frames, this precluded wide use of expensive isotope enriched probes such as 15N perdeuterated TEMPONE, because probes need to be continuously infused into the heart during acquisition, and this also precluded the study on how free radical distributions and organ functions change progressively over the time course of a given experiment. Many EPRI probes are rapidly reduced by the cellular redox defenses (e.g., glutathione), which silences the EPRI signal. While this is an advantage for studying cellular redox status, it is a challenge for imaging to acquire sufficient data before the signal is removed or washed out. There are some more expensive probes which have a stable free radical and thus very long lasting EPRI signal, but the focus of this work was to develop the hardware and software on an affordable probe which can be continuously infused into the heart during acquisition. Since there were only 64 field steps in the indirect acquisition scheme due to the long acquisition time, the resolution of acquired images was significantly limited. Consequently, applications of this original time intensive approach of EPRI gating have been impractical for most physiological applications.

Hence, there is a critical need to achieve fast gated EPRI capable of completing an acquisition of an image sequence of the cardiac cycle within a few minutes. This requires a major acceleration of the data acquisition and data transferring. The need for accelerated data transferring is because the current system transfers significant amount of redundant data of control waveforms from the control computer to acquisition electronics, and this contributes to the slowdown of acquisition speed. While spinning gradient (20,21) and rapid scan methods (22) improve the acquisition speed, there is still further potential to improve the acquisition speed by designing novel clocking schemes. Our previous work used a fixed-rate master clock to pace all A/D and D/A conversion activities of the data acquisition electronics (20,21). The fixed-rate oversampling acquisition scheme and acquisition software can achieve a minimum projection acquisition time of 1.3 second, which is too long to achieve direct gated cardiac EPRI.

The goal of the present work is to obtain gated 3D image data from a beating heart in minimum time suitable for physiological studies. In this article, a method of acquiring full 3D temporal frame sequence from a beating heart with good spatial and temporal resolution is described. First we describe the software and instrumentation developed to provide much faster acquisitions. Second the simulation phantom and isolated rat heart models of cardiac EPRI are described. Finally, the results are compared to those in the literature, including our previous work. The hardware and softaware described in this work along with developments in paramagnetic probes synthesis (23-26) provide valuable insights into cardiac physiology and pathology – like direct and simultaneous measurements of oxygen, and redox status, changes in pH and other functional information. With described developments, EPRI will gain ability to follow the changes of these parameters through the cardiac cycle. While EPR imaging provides critical functional information, gated MRI is able to provide precise anatomic registration and valuable complement functional information. With EPRI, combined with MRI in one instrument, powerful synergy of these two techniques can be achieved (27,28). Therefore next logical step for future EPRI development will be integration of developed EPR spatiotemporally-resolved 3D imaging with gated MRI.

METHODS

Fast Gated EPRI System Setup

In order to significantly increase EPR acquisition speed and in turn to achieve direct gated EPR imaging, the recently developed fast EPR acquisition scheme of adaptive heterogeneous clocking (AHC) significantly reduces communication between the host computer and gradient hardware by using different clocks to pace the A/D and D/A functions of our acquisition cards. Projections containing up to 4096 points can be acquired in as little as 10–20 ms using AHC. Near real-time acquisition can be performed for complex computer-generated gradient waveforms, which enable a variety of new sampling patterns (29). Figure 1 illustrates the gradients, field control, and clocking waveforms for fast EPRI acquisition with the AHC scheme. As shown in the figure, a slow D/A clock is used to generate the gradients and field control waveforms, so the amount of data to be transferred to the acquisition electronics can be significantly reduced. This helps to increase the overall acquisition speed. The D/A output clock rate is reduced to take advantage of the time constant of the sweep magnetic field, which is a result of the inductive load of the magnetic field hardware. The D/A output clock rate can be reduced and yet still produce a linear sweep of the magnetic field. A slower D/A clock reduces the amount of data to be transferred to the acquisition electronics, and we found that this sped up the acquisition with no loss in data fidelity. A fast A/D clock is used to acquire EPR projection data, to provide the high resolution of the projections. The A/D input clock rate is adaptive and adjusted according to the magnetic field sweep time to avoid unnecessarily high data rate of acquired EPR signals.

Figure 1. Gradients, field control, and clocking waveforms for fast EPR acquisition with the adaptive heterogeneous clocking scheme.

The fast EPRI acquisition scheme with AHC is capable of achieving acquisition time of as short as 5 ms per projection, enabling the typical projection acquisition times required for cardiac gating of 20–40 ms. This rapid projection acquisition paves the way for direct gated cardiac EPRI.

In direct gated cardiac EPRI, data I/O is grouped into multiple batches or cycles. Each batch/cycle corresponds to one cardiac cycle, as depicted in Figure 2 which illustrates the gradients, field sweeps, and pacing waveforms for direct fast gated EPRI acquisition. The waveforms were generated by the software in a similar way as described in our previous work (21,30). Within one cardiac cycle, there are multiple main magnetic field sweeps for generating multiple projections. These projections share the same gradient angle, and each of them belongs to an image frame in the cardiac cycle. In the next cardiac cycle, another set of multiple projections are acquired with another gradient angle, and so on.

Figure 2. Gradients, field sweep, and pacing waveforms for direct fast gated EPR acquisition.

In addition to outputting gradients and field sweep waveforms, the EPR acquisition computer also outputs waveforms for pacing a phantom or isolated heart, and the pacing waveform is synchronized with all other waveforms to ensure correct acquisition. The pacing waveform used for isolated heart studies is a pulse sequence which is preprogrammed with fixed amplitude and width, and is fed into an electric stimulator. The rising edges of the pacing pulses trigger the electric stimulator to output a synchronized sequence of high-amplitude short pulses with adjustable amplitude and width, which are in turn sent to the isolated heart to stimulate it. It was found that, when pacing a phantom using an electric pump, a sinusoidal waveform yielded the best motion of the phantom. Therefore, a sinusoidal waveform was used for pacing the phantom.

Between the adjacent batches of the grouped EPR projection acquisitions, there is a between-cycle time interval, or between-cycle pause, which is typically about 120 ms long for a 3 GHz PC with a PCI bus. The EPR acquisition PC uses this between-cycle pause to import acquired projection data from acquisition electronics, perform preliminary data processing, generate waveforms needed for the next batch of acquisition, and output them to the acquisition electronics. The acquisition software also uses this between-cycle pause to accept and respond to user requests such as pause or abort acquisition.

Figure 3 illustrates the block diagram of the direct fast gated EPR imaging system. In the system, a PC with 3 PCI expansion slots is used as the imaging/control acquisition computer. Three Keithley KPCI-3116 multifunction data I/O boards are plugged in the PCI expansion slots in the acquisition (16) computer, and are used as the main data I/O electronics. They communicate with the acquisition computer through the PCI bus on the PC.

PCI Bus

Pacing wires to Heart

Pacing Tubing to Phantom

Figure 3. Block diagram of the setup for the direct fast gated EPR imaging system.

Each Keithley KPCI-3116 card has two D/A output channels and can output two waveforms; it also has multiple A/D input channels. In the system, we use Board #0 to output waveforms for Gradient X and Gradient Y, Board #1 to output waveforms for Gradient Z and center magnetic field, and Board #2 to output waveforms for sweep magnetic field and pacing signals. The gradient and field control waveforms are sent to the current amplifiers in the EPR imaging system to generate required magnetic field gradients and the sweeping magnetic field. We use the first A/D input channel on Board #1 to acquire EPR projection data, and the acquired data are transferred to computer memory for processing, image reconstruction and storage on hard drive. The clock pins on the three KPCI-3116 cards are interconnected and synchronized to ensure correct data I/O. The EPR signal to be acquired by the A/D input channel on Board #1 is generated by a newly-constructed highly-sensitive dual-frequency resonator intended for the EPR/NMR co-imaging system (27,28,31,32). The pacing waveform from Board #2 is sent to different devices depending on whether to pace a phantom or an isolated heart.

Heart Phantom Setup

A phantom consisting of a 50 ml conical plastic bottle filled with 1.0 mM aqueous TEMPONE and a latex balloon was prepared to validate the fast gated EPRI technique (Figure 4). The latex balloon simulates the left ventricular balloon in the isolated heart by expanding and contracting with a motion similar to cardiac cycle of a beating heart with a tidal volume change of 0.25 ml over a 500 ms interval. The balloon is attached to a rubber chamber, which is compressed by an electric impeller to serve as a pump that is driven by a power amplifier controlled by a sinusoidal pacing waveform generated by the acquisition computer and synchronized to the data acquisition.

Figure 4. Block diagram of a paced phantom with supporting devices.

When pacing a phantom, a sinusoidal waveform from Board #2 is fed to a power amplifier, and then the amplified sinusoidal waveform is used to power the electric pump, whose pumping causes the phantom balloon to contract and expand. In experiments, 3D spatial gated images of the phantom described above were obtained.

During the acquisition, the center magnetic field strength was 415 Gauss, the magnetic field sweep range was 19 Gauss, the modulation frequency was 100 kHz and the modulation amplitude was 0.63 Gauss. The gradient angles were generated using the traditional sampling strategy for filtered backprojection with an equal linear angle increment in the logical X-Y plane and also between the X-Y plane and the Z axis (16,33). The number of projection angles, range and increments in the steps were equal in three gradient directions, so the acquired 3D data set had isotropic image resolution. The reconstruction weighted the projections appropriately for filtered backprojection. The heart phantom was paced at 2.0 Hz, the magnetic field sweep time and EPR projection acquisition time are both 50 ms. Ten projections of the same gradient angle were obtained during each cardiac cycle (500 ms). A total of 7840 projections were acquired during continuous 784 cycles, resulting in ten 3D cardiac frames and 784 projections for each frame. The acquired image sequences were post-processed with dynamic range compression, interpolation, smoothing, thresholding and color mapping for better visualization.

Preparation of Isolated Rat Heart

Figure 5 illustrates the setup of the paced isolated rat heart with supporting devices. Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were used and were euthanized with sodium-pentobarbital (30–50 mg/kg) and heparanized (0.1 mL of 1000 IU/kg) via an IP injection. Once the rat was deeply anesthetized, a thoracotomy was performed to facilitateexcision of the heart. The aorta was cannulated and perfused in a retrograde manner with Krebs bicarbonate perfusate consisting of 117 mM NaCl, 24.6 mM NaHCO3, 5.9 mM KCl, l.2 mM MgC12, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 16.7 mM glucose bubbled with 95% O2, and 5% CO2 under constant pressure of 80 mmHg. The temperature of the heart was maintained at 37 ± 1 ºC. The imaging probe was 4-oxo-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-l-oxyl (TEMPONE), which was infused into the rat heart at a concentration of 4 mM which is often used in EPRI and was proved not to be toxic and well tolerated in vivo. (34).

Figure 5. Block diagram of a paced isolated heart with supporting devices.

The left atrium was slit and a small latex balloon filled with 3 mM ascorbate was inserted into the left ventricular cavity through the mitral opening; allowing for continuous measurement of contractile function (LVDP, EDP, ESP, HR and dP/dt). The balloon was initially inflated via a syringe with a volume sufficient to produce an end-diastolic pressure of 8–12 mmHg. Two thin copper wires were connected to the left atrium and left ventricle to function as pacing electrodes. The heart was placed inside the cylindrical chamber of a specially designed holder. The inner diameter of the chamber was 25 mm. The holder was horizontally placed in the center of the EPR resonator with the isolated heart positioned at the center of the resonator. The heart was paced at 150 bpm (2.5 Hz) to 300 bpm (5 Hz) depending on the heart’s intrinsic rate, using a Grass SD9 electric pulse stimulator (Grass Instrument, Co., Quincy, MA). EPRI acquisitions were then performed on the heart, while continuous pacing and perfusion were maintained. The left ventricular pressure and the heart rate were monitored continuously throughout the experiment to ensure that complete synchronous capture was maintained by the pacing stimulator. Balloon pressure was monitored to ensure the heart was beating properly. The pressure waveform was normal and not the focus of this manuscript.

In order to best image of the paced isolated heart, a special setup was developed as illustrated in Figure 5. Isolated rat heart was placed into a horizontal position into the sample holder . The space between heart and cylindrical holder was filled the wash fluid which is a solution of 10% glucose with 5 mM sodium ascorbate. Wash fluid was continiously pumped around the heart at a flow rate ~10 fold higher than that of the heart perfusion. The wash fluid efficiently removes the paramagnetic label from outside of the heart.and clear the effluent TEMPONE. Presence of the glucose solution around the heart unloaded the weight of the heart, reduced microwave loss compared to the highly conductive perfusate and maintained a constant microwave load of the resonator, reducing oscillations of the coupling and thus attenuating heart beat-dependent sensitivity of the resonator. Ascorbate rapidly reduced TEMPONE to EPR silent nitroxylamine which eliminated the EPRI signal outside of the heart and provided a sharp delineation of the myocardium. The wash fluid also controlled the temperature of the heart maintained at 37 ± 1 ºC. In order to synchronize data acquisition with the cardiac contractile cycle, the heart was paced by an electric stimulator which is triggered by the synchronizing signal from the acquisition electronics.

During the acquisition, the center magnetic field strength was 410 Gauss, the magnetic field sweep range was 25 Gauss, the modulation frequency was 100 kHz and the modulation amplitude was 1 Gauss. The number of projection angles, range and increments in the steps were equal in three gradient directions, so the acquired 3D data set had isotropic image resolution. The rat hearts were paced at 2.5 Hz, the magnetic field sweep time and EPR projection acquisition time were both 40 ms. Ten projections of the same gradient angle were obtained during each cardiac cycle (400 ms). A total of 10240 projections were acquired during continuous 1024 cycles, resulting in ten 3D cardiac frames and 1024 projections for each frame. The acquired image sequences were post-processed in the same way as the phantom images.

RESULTS

Phantom Studies

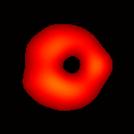

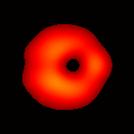

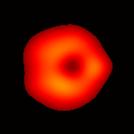

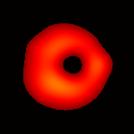

Electron paramagnetic resonance imaging (EPRI) of a test-phantom was performed in order to optimize imaging parameters and determine the limits of the developed gated imaging modality for studies of beating isolated hearts. The effects of projection acquisition time, phantom cycle length, and gradient settings on projections and image quality were studied. Figure 6(a) shows a slice of an acquired 3D image of the phantom. It illustrates the structure of the phantom, scale, and the color map used for visualization. Consistent, good quality 3D image sequences of a paced phantom were acquired using gated and fast EPRI (Figure 7).

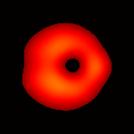

Figure 6. Gated image slices of the heart phantom and perfused rat heart. (a) Coronal slice of an acquired 3D image of the phantom. (b) Coronal slice of an acquired 3D image of an isolated heart.

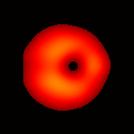

The total data acquisition time for ten 3D frames was 7.5 minutes. Figure 7(a) shows a frame sequence of the coronal view of the heart phantom during a cardiac cycle, and Figure 7(b) shows a frame sequence of the transverse view.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0~50 ms |

50~100 ms |

100~150 ms |

150~200 ms |

200~250 ms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

250~300 ms |

300~350 ms |

350~400 ms |

400~450 ms |

450~500 ms |

|

(a) Coronal View

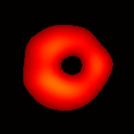

(b) Transverse View Figure 7. Gated image slices of a heart phantom. (a) Frame sequence of a coronal slice of the heart phantom over a cardiac cycle. (b) Frame sequence of a transverse slice. Imaging parameters: magnetic field sweep time = 50 ms; cardiac rate = 2.0 Hz; cardiac cycle = 500 ms; # of frames per cardiac cycle = 10; # of projections = 28 × 28 = 784; Acquisition time ≈ 7.5 min; center magnetic field = 415 Gauss; magnetic field sweep range = 19 Gauss; modulation frequency = 100 kHz; modulation amplitude = 0.63 Gauss. |

The maximum volume displacement of the balloon observed in the image data between Frame 1 and Frame 6 was about 0.25 ml, as expected. The image sequence successfully captured the cyclical contraction/expansion of the paced phantom balloon, and the free radical distribution at a voxel resolution of about 0.5 mm. With the further increase of cycle frequency, images showed that the phantom balloon had smaller excursions, but the image quality remained good with projection acquisition times as short as 10 ms and the total acquisition time as short as 1 minute.

Previously reported projection times typically range from several seconds to tens of seconds (9,19). The fast EPR acquisition technique enabled by AHC can achieve a projection acquisition time as short as 5 ms with 1024 data points. The typical projection acquisition time used in the fast EPRI is 20–40 ms, and the typical total time for acquiring a 3D image is 5–10 seconds.

Gated Imaging of Isolated Rat Heart

Figure 6(b) shows a slice of an acquired 3D image of an isolated heart. It illustrates the anatomical structure of the heart. The aorta is identified at the upper-left corner. The bright yellow region in the middle-left part of the heart is identified as the right ventricle, because the perfusate effluent collects in the right ventricle generating stronger signal. The dark void to the right is the latex balloon inserted in the left ventricular cavity. The grayish column above the balloon is identified as the plastic tubing connected to the balloon. The apex of the heart is seen at the bottom of the image.

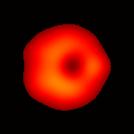

The total data acquisition time for ten 3D frames was 8 minutes. We have also demonstrated that, if the requirement on spatial resolution is reduced by acquiring only 256 projections (which is still greater than the 144 projections reported in our previous work (19); in addition, each projection contains 1024 data points as compared to 64 data points in the previous work), and if the heart is paced at 5 Hz, then the total acquisition time of 3D gated imaging is about 55 seconds, as compared to 64 minutes previously reported by us (19). Figure 8(a) shows a frame sequence of the coronal view of a paced heart during a cardiac cycle, and Figure 8(b) shows a frame sequence of the transverse view. It can be seen that the image sequence has successfully captured the cyclical contraction/relaxation of the paced isolated heart and the free radical distribution at a voxel resolution of about 0.5 mm. During systole the left ventricular cavity clearly reduces its size, and the left ventricular wall is also significantly thickened. Gated imaging of isolated rat heart with magnetic field sweep time of 20 ms and cardiac rate of 5 Hz was also conducted. These imaging parameters are also suitable for in vivo studies. The acquired images with this sequences had comparable quality. However, the excursion of the balloon motion in such image sequences is smaller than that shown in Figure 8, because the heart pacing rate was much faster.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0~40 ms |

40~80 ms |

80~120 ms |

120~160 ms |

160~200 ms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

200~240 ms |

240~280 ms |

280~320 ms |

320~360 ms |

360~400 ms |

|

(a) Coronal View

(b) Transverse View Figure 8. Gated image slices of perfused rat heart over the cardiac cycle. (a) Frame sequence of a coronal slice of a paced isolated heart. (b) Frame sequence of a transverse slice. Imaging parameters: magnetic field sweep time = 40 ms; cardiac rate = 2.5 Hz; cardiac cycle = 400 ms; # of frames per cardiac cycle = 10; # of projections = 32 × 32 = 1024; Acquisition time ≈ 8 min; center magnetic field = 410 Gauss; magnetic field sweep range = 25 Gauss; modulation frequency = 100 kHz; modulation amplitude = 1 Gauss. |

The half-lives of EPR probes such as nitroxide radicals are generally short in vivo, ranging from 1 to 30 minutes (7,35-37). Therefore, the acquisition speed is a key factor in in vivo EPR imaging and spectroscopy, and the capability of acquiring a gated 3D image sequence within two minutes significantly increases the applicability of the fast gated EPR acquisition technique. The fast EPR acquisition technique that we developed is capable of accelerating acquisition speed while maintaining reasonable signal to noise ratio, because the fast scan also efficiently suppresses motional and other noises with frequencies lower than the scan rate.

DISCUSSION

Direct gated cardiac EPRI has been successfully achieved with the fast EPR acquisition enabled by adaptive heterogeneous clocking. A sequence of 3D images depicting the motion of the beating heart during the cardiac cycle can be acquired in as short as a few minutes. The fast gated EPRI technique not only enables the study on how free radical distribution and organ functions evolve during the cardiac cycle, but also provides sharper images without the blurring effect caused by cardiac motion.

In previous work, while great progress has been made in the development of instrumentation and techniques for EPRI, it has become clear that long image acquisition time previously required for this technique was a fundamental limitation of this imaging modality. The fast EPRI with AHC is fast enough for the study of the beating heart and its physiology. Although pulsed EPR can also acquire images even much faster, the short T1 values of most EPR probes such as nitroxides limit its applicability (38-40).

The performance of the fast EPRI system has been evaluated in a series of phantom and isolated rat heart studies. Since CW EPRI is not slice-selective, in order to acquire quantitative 3D information about the spatial distribution of the paramagnetic species, a full 3D acquisition of the whole field of view (FOV) that includes the object must be performed. The AHC-based fast EPRI technique can acquire a 3D image within a time period comparable to that of 3D MRI. While others have developed high performance hardware-based gradient waveform generation using function generators (41,42), AHC is based entirely on software-generated waveforms, allowing much more flexibility in designing novel acquisition schemes. The fast EPR imaging system presented here greatly facilitates the efficiency and increases the applicability of EPRI. The developed instrumentation and software were applied to studies of isolated beating rat heart paced up to 300 beats per minute. To apply this technique for actual in vivo studies with gated imaging of intact hearts which can beat with irregular frequency about 320-480 bpm, additional challenges like acceleration of acquisition time, variations in the timing of R-R interval, lung motion on top of cardiac motion should be overcome. Technical parameters of hardware allow further decrease the projection scan time, therefore the developments will have to focus on software improvements like retrospective gating which will be subject of our future work.

In conclusion, a fast, gated EPRI acquisition was developed. The fast gated EPRI technique opens the way for numerous potential biomedical applications. This technique enables measurement and mapping of myocardial free radical concentration and metabolism as a function of the cardiac contractile cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported in part by NIH grants EB0890 and EB4900. David Johnson was supported by NIH training grant F32 EB012932.

REFERENCES

1. Ishida S, Kumashiro H, Tsuchihashi N, Ogata T, Ono M, Kamada H, Yoshida E. In vivo analysis of nitroxide radicals injected into small animals by L-band ESR technique. Phys Med Biol 1989;34:1317–1323.

2. Berliner L, Wan X. In vivo pharmacokinetics by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med 1989;9:430–434.

3. Alecci M, Colacicchi S, Indovina P, Momo F, Pavone P, Sotgiu A. Three-dimensional in vivo ESR imaging in rats. Magn Reson Imaging 1990;8:59–63.

4. Takeshita K, Utsumi H, Hamada A. ESR measurement of radical clearance in lung of whole mouse. Biophys Res Commun 1991;177:874–880.

5. Kuppusamy P, Chzhan M, Vij K, Shteynbuk M, Lefer DJ, Giannella E, Zweier JL. 3-D spectral-spatial EPR imaging of free radicals in the heart: A technique for imaging tissue metabolism and oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:3388–3392.

6. Kuppusamy P, Chzhan M, Zweier JL. Development and optimization of three-dimensional spatial EPR imaging for biological organs and tissues. J Magn Reson B 1995;106:122–130.

7. Alecci M, Ferrari M, Quaresima V, Sotgiu A, Ursini CL. Simultaneous 280 MHz EPR imaging of rat organs during nitroxide free radical clearance. Biophys J 1994;67:1274–1279.

8. Kuppusamy P, Wang P, Zweier JL. Three-dimensional spatial EPR imaging of the rat hearts. Magn Reson Med 1995;34:99–105.

9. Zweier JL, Chzhan M, Samouilov A, Kuppusamy P. Electron paramagnetic resonance imaging of the rat heart. Phys Med Biol 1998;43:1823–1835.

10. Kuppusamy P, Chzhan M, Samouilov A, Wang P, Zweier JL. Mapping the spin density and lineshape distribution of free radicals using 4D spectral-spatial EPR imaging. J Magn Reson B 1995;107:116–125.

11. Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Cardiac applications of EPR imaging. NMR Biomed 2004;17:226–239.

12. Gilbert BC, Davies MJ, Murphy DM. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. 2002.

13. Deng Y, He G, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Deconvolution algorithm based on automatic cutoff frequency selection for EPR imaging. Magn Reson Med 2003;50(2):444-448.

14. Deng Y, Petryakov S, He G, Kesselring E, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Fast 3D spatial EPR imaging using spiral magnetic field gradient. J Magn Reson 2007;185(2):283-290.

15. Kuppusamy P, Chzhan M, Vij K, Shteynbuk M, Lefer DJ, Giannella E, Zweier JL. Three-dimensional spectral-spatial EPR imaging of free radicals in the heart: a technique for imaging tissue metabolism and oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91(8):3388-3392.

16. Eaton GR, Eaton SS, Ohno K. EPR imaging and in vivo EPR. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991.

17. Zweier JL, Thomson-Gorman S, Kuppusamy P. Measurement of oxygen concentrations in the intact beating heart using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy: A technique for measuring oxygen concentrations in situ. J Bioenerg Biomernbr 1991;23:855–871.

18. Testa L, Gualtieri G, Sotgiu A. Electron paramagnetic resonance imaging of a model of a beating heart. Phys Med Biol 1993;38:259–266.

19. Kuppusamy P, Chzhan M, Wang P, Zweier JL. Three-Dimensional Gated EPR Imaging of the Beating Heart: Time-Resolved Measurements of Free Radical Distribution During the Cardiac Contractile Cycle. Magn Reson Med 1996;35:323–328.

20. Deng Y, He G, Petryakov S, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Fast EPR imaging at 300 MHz using spinning magnetic field gradients. J Magn Reson 2004;168:220–227.

21. Deng Y, Petryakov S, He G, Kesselring E, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Fast 3D spatial EPR imaging using spiral magnetic field gradient. J Magn Reson 2007;185:283–290.

22. Stoner JW, Szymanski D, Eaton SS, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton GR. Direct-detected rapid-scan EPR at 250 MHz. J Magn Reson 2004;170:127–135.

23. Liu Y, Villamena FA, Zweier JL. Highly stable dendritic trityl radicals as oxygen and pH probe. Chem Commun (Camb) 2008(36):4336-4338.

24. Liu Y, Villamena FA, Sun J, Wang TY, Zweier JL. Esterified trityl radicals as intracellular oxygen probes. Free Radic Biol Med 2009;46(7):876-883.

25. Liu Y, Villamena FA, Song Y, Sun J, Rockenbauer A, Zweier JL. Synthesis of (14)N- and (15)N-labeled Trityl-nitroxide Biradicals with Strong Spin-Spin Interaction and Improved Sensitivity to Redox Status and Oxygen. J Org Chem 2010.

26. Liu Y, Villamena FA, Rockenbauer A, Zweier JL. Trityl-nitroxide biradicals as unique molecular probes for the simultaneous measurement of redox status and oxygenation. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46(4):628-630.

27. He G, Deng Y, Li H, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. EPR/NMR co-imaging for anatomic registration of free-radical images. Magn Reson Med 2002;47:571–578.

28. Samouilov A, Caia GL, Kesselring E, Petryakov S, Wasowicz T, Zweier JL. Development of a hybrid EPR/NMR coimaging system. Magn Reson Med 2007;58:156–166.

29. Chen Z, Johnson D, Caia G, Sun Z, Petryakov S, Samouilov A, Zweier JL. Fast EPR Acquisition with Adaptive Heterogeneous Clocking (AHC). Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 2011;19.

30. Deng Y, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Progressive EPR imaging with adaptive projection acquisition. J Magn Reson 2005;174(2):177-187.

31. Petryakov S, Samouilov A, Kesselring E, Caia GL, Sun Z, Zweier JL. Dual frequency resonator for 1.2 GHz EPR/16.2 MHz NMR co-imaging. J Magn Reson 2010;205:1–8.

32. Hirata H, He G, Deng Y, Salikhov I, Petryakov S, Zweier JL. A loop resonator for slice-selective in vivo EPR imaging in rats. J Magn Reson 2008;190:124–134.

33. Ahmad R, Clymer B, Vikram DS, Deng Y, Hirata H, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P. Enhanced resolution for EPR imaging by two-step deblurring. J Magn Reson 2007;184(2):246-257.

34. Kuppusamy P, Wang P, Zweier JL. Three-dimensional spatial EPR imaging of the rat heart. Magn Reson Med 1995;34(1):99-105.

35. Yokoyama H, Lin Y, Itoh O, Ueda Y, Nakajima A, Ogata T, Sato T, Ohya-Nishiguchi H, Kamada H. EPR imaging for in vivo analysis of the half-life of a nitroxide radical in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of rats after epileptic seizures. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999;27(3-4):442-448.

36. Kuppusamy P, Wang P, Shankar RA, Ma L, Trimble CE, Hsia CJC, Zweier JL. In vivo topical EPR spectroscopy and imaging of nitroxide free radicals and polynitroxyl-albumin. Magn Reson Med 1998;40(6):806-811.

37. Kuppusamy P, Wang P, Zweier JL, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Ma L, Trimble CE, Hsia CJC. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Imaging of Rat Heart with Nitroxide and Polynitroxyl-Albumin. Biochemistry 1996;35(22):7051–7057.

38. Hyodo F, Matsumoto S, Devasahayam N, Dharmaraj C, Subramanian S, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Pulsed EPR imaging of nitroxides in mice. J Magn Reson 2009;197(2):181-185.

39. Murugesan R, Cook JA, Devasahayam N, Afeworki M, Subramanian S, Tschudin R, Larsen JA, Mitchell JB, Russo A, Krishna MC. In vivo imaging of a stable paramagnetic probe by pulsed-radiofrequency electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med 1997;38(3):409–414.

40. Murugesan R, Afeworki M, Cook JA, Devasahayam N, Tschudin R, Mitchell JB, Subramanian S, Krishna MC. A broadband pulsed radio frequency electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometer for biological applications. Rev Sci Instrum 1998; 69:1869–1876.

41. Sato-Akaba H, Kuwahara Y, Fujii H, Hirata H. Half-Life Mapping of Nitroxyl Radicals with Three-Dimensional Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Imaging at an Interval of 3.6 Seconds. Anal Chem 2009;81:7501–7506.

42. Joshi JP, Ballard JR, Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Rapid-scan EPR with triangular scans and fourier deconvolution to recover the slow-scan spectrum. J Magn Reson 2005;175:44–51.